For some time, a group has been meeting in the Fab Lab to build a solar charge controller called „Libre Solar“. We talked to Martin Jäger, who started the project, and explains exactly what it is all about.

Fab Lab Fabulous St. Pauli: Martin, you have developed a solar charge controller and matching electronics for battery management. Similar devices already exist on the market. Why did you take the liberty to reinvent the wheel? What’s so special about your electronics?

I started with the project because I wanted to understand how electronics work. I had little to do with it before and wanted to get started with an exciting, practically usable circuit. The peculiarity is that it is open source, so you can expand the devices themselves. You can read data via an interface and program the boards freely. The schematics can also be downloaded and rebuilt.

…

What can you use the devices for?

Martin: The solar charge controller is the link between a solar cell and a battery. This an be, for example, a lead-acid battery like in a car. The charge controller converts the high voltage of the solar cells to the lower voltage of the battery, taking care not to overcharge or discharge the battery too deeply. There is a load connection to which the consumers are connected. It would switch off as soon as the battery has too low a voltage.

If you want to use batteries with lithium-ion cells, monitoring and over-charging protection is even more important. In addition, the cells must always be kept at a similar voltage, by so-called „balancing“. That’s why you need a battery management system.

If you want to use batteries with lithium-ion cells, monitoring and over-charging protection is even more important. In addition, the cells must always be kept at a similar voltage, by so-called „balancing“. That’s why you need a battery management system.

For communication between the components of the small power system, there is a communication protocol based on the CAN-Bus. So battery management can tell the charge controller, „I want to charge to a certain voltage now.“

How many cells can you connect?

Up to five. However, four cells make sense because you can achieve the same voltage with four lithium iron phosphate cells as a 12 volt battery from the car.

However, standard slightly higher voltage standard laptop cells rated at 3.7 volts per cell can also be used.

At which voltages are solar modules typical?

Large roof modules usually have 60 cells. One cell has 0.5 volts, so a module has a total of 30 volts. Batteries are at 12 volts, so you have to regulate the voltage to a lower level.

How did you go about designing? How could you use the Fab Lab for this?

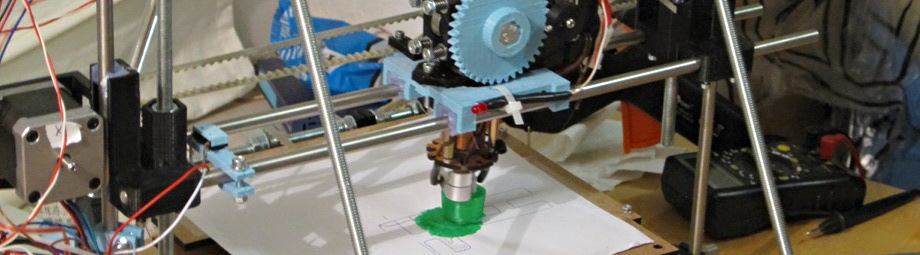

You need a board on which you have to solder the individual components. However, the board is complicated to manufacture itself because it has very small structures and many small plated-through holes. If you make the board by hand, you would have to drill every single hole. That would be too complicated. That’s why I ordered the board on the Internet, but here in the Fab Lab we developed ideas with Axel on how to apply the solder paste sensibly. This is done with a stencil, which is cut out on the laser cutter. You cut out of the material the places where you want to apply solder paste on the board.

There is also a so-called reflow oven, in which you can solder the components that have been applied to the places with the solder paste.

What were the challenges in the project?

First of all to get into the matter. Which components from the huge selection on the market do you take? Then the production. With power electronics, where a lot of electricity flows, breadboards are of little use. You need to manufacture boards and solder solder them properly. The Fab Lab with the reflow oven was very helpful.

Why did you choose to publish the results of your work and make them available to others?

Because I hope that others may find the idea good and want to contribute to it. That already happend. There are already some people approaching me. There is also a lot of support on the internet if you have questions about electronics. Arduino is also open source. I hope that in the future an open source environment could also be established for energy systems. That could also be interesting for developing countries.

You started with an Arduino?

Yes, but at some point I pushed the boundaries of the classic Arduino and then switched to a 32-bit microcontroller.

What advantages and disadvantages do you see in Open Source?

The advantage that many people can join and so better products can arise. Disadvantage, that someday somebody distributes this commercially, without participating in the further development.

Recently, a Hamburg university group has recreated the Libre Solar system. How did that happen?

That came about Oliver from the association Open Source Ecology Germany, with whom I once had built a battery management board here in the Fab Lab. He published something about it, and so one of the students became aware of the project. He contacted me and we said: good idea if you do it together. Then I supported that.

What did you learn?

The first step was to build the electronics, using a lasercutted stencil and solder everything. We have seen that the manual assembly of the boards is a certain effort. The students study automation technology and renewable energies. But even in these courses you do not really learn how to design circuits or apply electronics in practice.

If I want to use this now: Do I have to do the electronics myself? What does it cost?

At the moment you have to do it yourself and solder everything on your own. The costs are approximately, if ordered in Germany, at 40 euros for a board. For the components of the charge controller are still 50 to 60 euros on top.

The problem with electronics is that you have to comply with a lot of guidelines if you want to sell them legally. With kits this is still possible, but if you sell a finished board, you must comply with the Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Directive (WEEE Directive), which is represented by a small crossed-out wheelie bin symbol. And you have to perform electromagnetic compatibility tests to print a CE logo on the board. It all costs a lot of money. That’s why I have not done that yet. Now I want to cooperate with a company for the garbage can symbol, and for the electromagnetic compatibility I hope to cooperate with the university.

You created the board with the KiCAD-software, which is also open source, and had a lot of work with it.

I had previously worked with Eagle, which was then bought by Autodesk. The free license is very limited now, the full use was only possible with a subscription. It’s also cloud-based, which does not work on the train, for example. I disliked this licensing policy.

Then I bit into the bullet, like many other open source users, and acquired new software. That was KiCad. In retrospect, I have not regretted that, because KiCad offers many better features.

How much higher is the effort on KiCAD compared to Eagle?

Not higher, if you know how both run. It’s best to work in KiCAD right away.

How can interested parties support the project?

Contact me, and then we’ll see. When it’s time for me to offer the first hardware, then it’s about optimizing the software – the communication protocol, the user interface, the representation of the solar yield. If someone is more interested in hardware development, we can look to build a PCB in the Fab Lab.

Companies can also contact you?

Sure!

Where can you use the electronics?

For example, in caravans to charge a 12 volt battery with a solar cell. Then in developing countries, where so far the focus is not on low cost, but on versatility that you can continue to work with it.

Another case would be „guerrilla photovoltaic systems“ on the balcony. That is being legalized. You could then provide batteries. At the moment, one would have to buy a proprietary inverter to feed the electricity into the 220-volt AC grid. Maybe there will eventually be an open source inverter.

Does the charge controller also work for wind or pedal power?

Pedal force is doing just fine. If you take a brushless DC motor, as used in many e-bikes, you can use it as a generator. You just have to build a simple rectifier out of a few diodes, and then you can use the charge controller with a bike or with a wind turbine. You can also charge bicycle batteries with the charge controller.

Are quality and environmental standards important to you when purchasing boards?

Sure! That’s why I do not order my boards in China. I will not have the manufacturing done in China either. There are already companies that have good working conditions and pay fairly, but then you have to travel there and clarify everything. That’s why I’ll do that in Germany first.

Unfortunately, electronics is a difficult area overall in terms of environmental and social standards. Solder is produced under bad conditions. It was also one of the Fairphone’s materials that was changed to fair sources. There is the club Fair lötet …

… which is also linked to the Fab Lab …

which offers fair solder. However, they have so far no solder paste for SMD soldering on offer. The supplier for the Fairphone is a company from Austria. At the moment, it would only be possible to produce the first prototypes fairly with a great deal of effort. So while I’m not in the right production, I still use conventional solder paste.

Looking ahead: where does Libre Solar stand in two years?

Then hopefully the charge controller can be ordered on the internet with just a few clicks to make it easier to get started without soldering. And we want to bring the open source idea to developing countries, because we are in contact with a university in Dakar. It would be a dream, if that happened in two years.

Links: